I stepped outside to talk to the police officers who’d responded to a call about me. When I opened my van/home door to retrieve my ID, an officer poked his unmasked head inside and shone his flashlight around, reflecting the laundry, dinner dishes, my hastily made bed.

“Can you back up, please?” I said, not rudely but firmly, aware of my privilege. Without that pass I was born with—“white”—even such a mild reproach would carry a possibility of great peril I was blissfully free of.

My 2-year-old nieces, Lucy and Claire, learn #BlackLivesMatter, from their mom, Cassie.

This writing is to white readers, especially those who believe racism is isolated, not near you, or a sad remnant of the past. Most of you are kind. When you interact face-to-face with a person of color, you’re likely warmhearted. I’m begging that we move beyond defensiveness—“not me, not my community”—and see that, despite our kindness, we live in a society that’s unrelentingly unjust. We enjoy the benefits of our whiteness, while people of color perform exhaustive and exhausting mental, emotional, and physical gymnastics to live safely. And far too many, nevertheless, don’t.

We’re all part of the fabric of the society (the white supremacy) that makes that so. To be part of the change that will come requires that we first see the truth. To that end, please consider these four premises (better yet, read or listen to voices who understand them far better than me):

The United States is a white supremacist society. (Robin DiAngelo, White Fragility)

Race sorted by skin color is a societal tool to make “palatable” horrific atrocities. (Dorothy Roberts, Fatal Invention)

People not seen as white have experienced “entrenched suffering” since the creation of this society. (Audra D. S. Burch, in “Special Episode: The Latest from Minneapolis,” NY Times, The Daily; see also James Baldwin, The Fire Next Time; Ta-Nehisi Coates, Between the World and Me; Angie Thomas, The Hate U Give; “A Weekend of Pain and Protest,” NY Times, The Daily; Ijeoma Oluo, So You Want to Talk about Race.)

If you’re asking whether the looting as an offshoot of recent protests is wrong, “you’re asking the wrong question. (Trevor Noah, “George Floyd and the Dominos of Racial Injustice”)

I’ll elaborate.

Our white supremacist society

Vile, hooded violence. The “n” word. Foul hatred borne of greed or, its shadow, disenfranchisement and ignorance. These are terrible expressions of white supremacy. And also supreme is another word for better. The US society is founded and still functions on the premise that it’s better to be white.

It’s better to be white because, if we’re white, we can move through society without fear of injury, imprisonment, or death based on the color of our skin at the hands of the power structure that’s part of the social contract we’ve all agreed on. If we’re white, we can say things like, “We all belong to the human race,” and, “I don’t see color”; feel good about not being part of “the problem”; and, thus, gaslight ourselves and the people harmed by the problem daily.

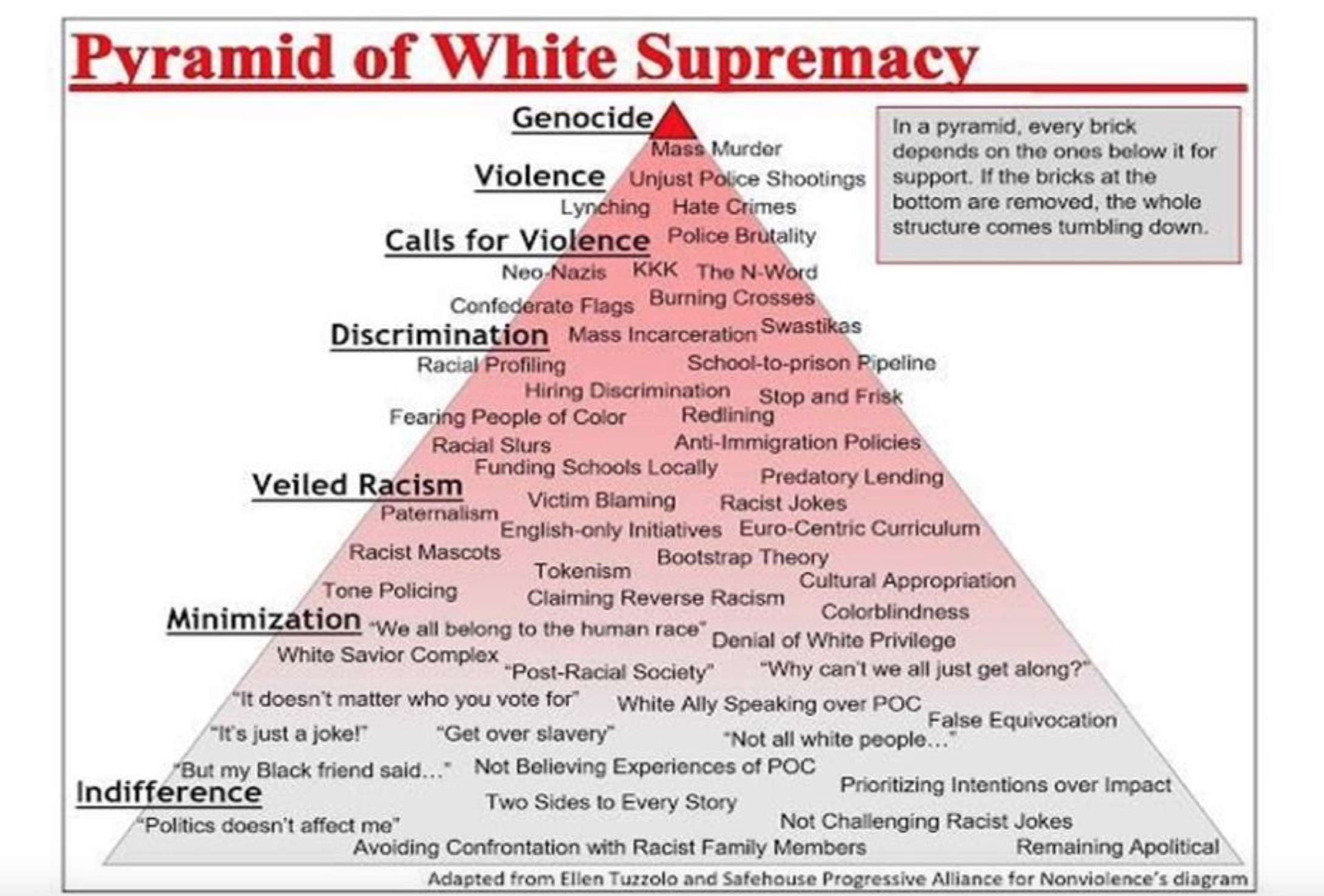

Adapted from Ellen Tuzzolo and Safehouse Progressive Alliance for Nonviolence’s diagram.

Race as an invention

When our society was built on slavery, the white men in charge claimed people with black skin were a different race—less intelligent, more aggressive, built stronger for physical labor and to feel less pain. In truth, people with black skin color are from and live all over the world and are part of many diverse cultures and experiences and communities. When our society was built on looting the land and lives of the native people, the white men in charge claimed them different—uncivilized, unable to grasp the concept of ownership of land, more unruly. The indigenous people of the United States comprise a vast variety of tribes and cultures and experiences.

Devaluation continues to be a tool of power to ease the collective conscience. The White House uses words like “illegal,” “alien,” and “invaders” to describe people attempting to migrate here, as separating aliens and caging illegal invaders is not the same as separating families and caging children. When angry, white protestors storm state capitols with assault rifles (arguably brandishing), the White House suggests governors make deals with the “good people” exercising their right to protest. When people of color and their allies storm the same capitols with handwritten signs, the White House calls them “thugs” and threatens, “When the looting starts, the shooting starts” (a phrase used in 1967 by Civil Rights era Miami police chief who had a long history of bigotry). Who gets the percussion grenades and pepper spray—thugs or good people?

The fruits of entrenched suffering

You are outraged by the murder of George Floyd. Hold this outrage in a part of your mind.

Now remember a time when you were enraged at the unfair treatment of your child or loved one. Recall what you dreamed of doing or saying to the snot-nosed brat whose cruelty brought tears, the insensitive teacher who didn’t take time to see the full truth, the jerk boss with the demeaning behavior.

What if you saw, in the face and body of George Floyd, the face and body of your son, your husband, your father, yourself? What if you knew there was a real possibility that any interaction with the police (or, for that matter, armed “vigilantes”) could change your life or end it in a flash? What if your son was five times more likely to go to prison than his white counterparts (NAACP)? What if you knew some pissed-off white woman could use your skin color as a weapon? What if you had to be on alert and on your best behavior always?

Imagine this. When you browse at a department store, you’re often tailed by security. It’s not unusual for your intellectual or economic accomplishments to be met with masked surprise. When you run with your (white) wife, you always run in front, lest you be seen as chasing her. You only walk certain neighborhoods with your young children, as alone, you might be perceived as a threat. Donning a hoodie comes with the risk of being mistaken for a criminal. You spill your gratitude nightly no one got nervous around your gentle giant (black) husband and called the police today. Your six-year-old daughter told you she didn’t want to leave you alone for your safety. (These are people’s realities, the last of George Floyd’s best friend, former NBA player, Stephen Jackson. The link is to a speech he gave, following a powerful speech by activist Tamika Mallory. )

Now imagine there’s a pandemic. People of your skin color are dying at least at twice the rate of white people (The Atlantic, June 2020; The Atlantic, April 2020). The virus doesn’t discriminate. Society does. Chronic, brutal inequities—less and lower-quality health access, greater rates of environmental pollution, denser living, greater likelihood of doing lower-paid “essential work”—have long plagued your black, Latino, and Native American communities. Imagine watching white people complain about their rights being infringed on because they’re asked to wear masks.

The wrong question

Power is only transferable “peaceably” by those who hold it. Consider that when, in 1920, white women received the right to vote, only white men could give that right (DiAngelo). If power isn’t shared peaceably, it will eventually be taken forcibly.

Now imagine you’ve tried to work “within the system” to change racial disparities your whole life. If you hear the bootstrap message—this wouldn’t be your reality if you were just better, stronger, worked harder—one more time, you’re going to scream. Your protests are hijacked by agitators, if not the hair-trigger fingers of the officers allegedly there to serve and protect your constitutional right to protest. Let’s say you choke on pepper spray, gasping for breath. Let’s say a rubber bullet slams into your neighbor, breaking skin and bone. Let’s say someone of your skin color knelt in quiet, peaceful, respectful protest during the national anthem and, in return, had his career taken from him and was called an unpatriotic traitor. Let’s say someone of your skin color chanted in prayer in defense of water and ancestral lands on a frozen night and was hammered with freezing water cannon blasts, threatened by snarling dogs. Let’s say the collective anger and pain and entrenched suffering bubble over and things get destroyed or looted by opportunists or people so distraught they’re about to break, and you’re told to behave—blamed once more. If you’d have just done something peaceful, quiet, and respectful, they might have listened.

When your derision is directed at looting and destruction of property, as if shaming an unruly child, as Trevor Noah said much more eloquently than I could, you’re asking the wrong question. You’re only imagining the bubble you live in. Remember your rage on behalf of a wronged loved one? If the wrong happened over and over and it became clear there would be no end no matter what you did, what wouldn’t you burn down to stop it? The question isn’t, Is this the wrong way? The question is, How can I help end the entrenched pain and suffering that has led to this?

Talk to the next generation about racism. Photo by Cassie Starley. Thanks, sis-in-law!

The right question: What can we white people do?

1. Get past shame and indignation.

Think of it like this. You’re told the foundation of an apartment complex you rent out (and live near) is rotting. You respond, “I’m not a bad person. I clean the complex all the time.” The tenants ask, “Please fix the rot before the building falls.” You say, “Why can’t we all just get along?” They demand the repair, and you get pissed. “I inherited the building. The foundation was already rotting. It’s the city’s pipes that leaked. Why are you calling me the bad guy?”

You’re missing the point. You’re goodness is irrelevant. The complex is rotting. It needs to be fixed. Please stop feeling judged or blamed or ashamed and start fixing the problem. (And stop shaming people who get enraged because the rot is threatening their and their loved ones’ lives.)

2. Listen to and seek out perspectives outside your own experience.

If a person of color tells you about his, her, or their experience, believe and listen. Period. Don’t ask your friends of color for explanations or solutions.

Follow activists like @tamikadmallory, @OsopePatrisse, @opalayo, @aliciagarza, @bellhooks,@Luvvie, @mharrisperry, @VanJones68, @ava, @thenewjimcrow, @Lavernecox @deray, @rachel.cargle, and @TaNehisiCoats. Just listen and learn. Period. “Pay lesser known activists like @thedididelgado here, Ally Henny here, and Lace on Race here for their teaching, time, and work” (from “75 Things White People Can Do for Racial Justice”).

Read and listen to books and videos. Along with the few I’ve linked here, check out this list, “Understanding and Dismantling Racism: A Booklist for White Readers” by Charis Books and More.

3. Talk to your kids.

The parents actively raising children who will continue the work of dismantling white supremacy and bigotry are heroes. Charis also has a list for kids, “Books to Teach White Children and Teens How to Undo Racism and White Supremacy.”

Listen to this 7-minute podcast in which All Things Considered Host Michel Martin talks to Jennifer Harvey about her book Raising White Kids. “‘Raising White Kids’ Author on How White Parents Can Talk about Race.”

Check out “How White Parents Can Use Media to Raise Anti-Racist Kids” by Common Sense.

4. Know the difference between bias (prejudice) and racism and stop believing in reverse racism. Know that ending white privilege doesn’t take from you; it shares with others (which benefits them and you).

Racial bias (prejudice) is when I have a judgment about or dislike you based on your skin color. Racism is when that judgment is backed by the power structure. I can be biased against or hold prejudices about white people, but those biases aren’t enforced by societal structures.

When white women (and black women finally in 1965) got the right to vote, the men didn’t lose their right to vote. I should be able to ask a police officer not to stick his head into my home uninvited (and, in the time of a pandemic, unmasked). I should be able to jog, commit a traffic violation, go to church, go shopping, wear whatever I want, protest injustice, and let loose without fear that, because of my skin color, I will be hurt or killed. I should be able to screw up royally and get arrested and face criminal charges, knowing that, when taken into custody, I will be protected and, when going to court, I will be treated fairly. And so should everyone who lives in our society.

5. Protest.

In the words of writer and activist Rachel Elizabeth Cargle, asking white women who marched with the Women’s march to show up now, “Don’t you understand that the only reason the Women’s March wasn’t violent is because the March was comprised of the types of (white) bodies the police are trained to protect? RACIAL JUSTICE IS A FEMINIST ISSUE.”

6. Donate.

Help protestors with bail funds. Among the many organizations and cities who need this help (all great), check out go.crooked.com/bailfunds. They’re splitting donations between 70+ community bail funds, mutual aid funds, and racial justice organizations.

Campaign Zero is working on 10 specific policy solutions to end police violence.

Black Visions Collective is a black, trans, and queer-led organization committed to dismantling systems of oppressions and violence.

Look for Go Fund Me campaigns for families who are suffering losses, such as Justice for Breonna Taylor.

There’s a good list in the Make a Donation section of, “How to Support the Struggle Against Police Brutality” (Claire Lampen, The Cut, May 31, 2020).

7. Document.

Learn how to safely record police interactions. (ACLU Apps to Record Police Conduct).

8. Speak up.

Hard conversations are hard. But if we, with our white passes, are too uncomfortable to speak truth to people around us who are perpetuating these disparities, whether consciously or not, what hope is there?

9. Stop believing you want to help but just don’t know how.

Do some of these “75 Things White People Can Do for Racial Justice” (Corinne Shutak, Equality Includes You, August 13, 2017).

Imagine if you and every white person you know did even one of these things every month for the next year.

“I have privilege as a white person because I can do all of these things without thinking twice:”

I can go birding (#ChristianCooper)

I can go jogging (#AmaudArbery)

I can relax in the comfort of my own home (#BothemSean and #AtatianaJefferson)

I can ask for help after being in a car crash (#JonathanFerrell and #RenishaMcBride)

I can have a cellphone (#StephonClark)

I can leave a party to get to safety (#JordanEdwards)

I can play loud music (#JordanDavis)

I can sell CDs (#AltonSterling)

I can sleep (#AiyanaJones)

I can walk from the corner store (#MikeBrown)

I can play cops and robbers (#TamirRice)

I can go to church (#Charleston9)

I can walk home with Skittles (#TrayvonMartin)

I can hold a hair brush while leaving my own bachelor party (#SeanBell)

I can party on New Years (#OscarGrant)

I can get a normal traffic ticket (#SandraBland)

I can lawfully carry a weapon (#PhilandoCastile)

I can break down on a public road with car problems (#CoreyJones)

I can shop at Walmart (#JohnCrawford)

I can have a disabled vehicle (#TerrenceCrutcher)

I can read a book in my own car (#KeithScott)

I can be a 10yr old walking with our grandfather (#CliffordGlover)

I can decorate for a party (#ClaudeReese)

I can ask a cop a question (#RandyEvans)

I can cash a check in peace (#YvonneSmallwood)

I can take out my wallet (#AmadouDiallo)

I can run (#WalterScott)

I can breathe (#EricGarner)

I can live (#FreddieGray)

I CAN BE ARRESTED WITHOUT THE FEAR OF BEING MURDERED (#GeorgeFloyd)

“White privilege is real. Take a minute to consider a black person’s experience today.”

—Adapted from Demcast staff, “I Have Privilege As a White Person Because I Can Do All of These Things without Thinking Twice,” Demcast, May 29, 2020. Some graphic content. Use discretion.

References and resources

ACLU. Apps to Record Police Conduct.

Baldwin, James. The Fire Next Time. Dial Press, 1963. First published in The New Yorker.

Burch, Audra D. S. In “Special Episode: The Latest from Minneapolis.” NY Times, The Daily. Podcast. Hosted by Michael May 31, 2020.

Charis Books and More. “Books to Teach White Children and Teens How to Undo Racism and White Supremacy.”

Charis Books and More. “Understanding and Dismantling Racism: A Booklist for White Readers.”

Coates, Ta-Nehisi. Between the World and Me. One World, 2015.

Demcast staff. “I Have Privilege As a White Person Because I Can Do All of These Things without Thinking Twice,” Demcast, May 29, 2020. Some graphic content. Use discretion.

DiAngelo, Robin. White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to talk about Racism. Beacon Press, 2018.

Filucci, Sierra. “How White Parents Can Use Media to Raise Anti-Racist Kids.” Common Sense Media, May 29, 2020.

Harvey, Jennifer. In “‘Raising White Kids’ Author on How White Parents Can Talk about Race.” All Things Considered. Podcast. Hosted by Michel Martin. May 31, 2020.

Lampen, Claire. “How to Support the Struggle Against Police Brutality.” The Cut, May 31, 2020.

Mallory, Tamika, and Jackson, Stephen. “Activists on Floyd Death.” Fox Carolina News. Facebook watch party. May 31, 2020.

NAACP. “Criminal Justice Fact Sheet.” 2020.

New York Times dispatchers. “A Weekend of Pain and Protest,” NY Times, The Daily. Podcast. Hosted by Michael Barbaro. June 1, 2020.

Noah, Trevor. “George Floyd and the Dominos of Racial Injustice.” The Daily Show with Trevor Noah. YouTube channel. May 29, 2020.

Oluo, Ijeoma. So You Want to Talk about Race. Seal Press, 2018.

Roberts, Dorothy. Fatal Invention: How Science, Politics, and Big Business Re-Create Race in the Twenty-First Century. The New Press, 2012.

Shutak, Corinne. “75 Things White People Can Do for Racial Justice” (Equality Includes You, August 13, 2017).

Thomas, Angie. The Hate U Give. Harper Collins, 2017.